Sweet Bolivia

By Deia Schlosberg

June 4, 2007

Villazon, Tupisa, Atocha, Cerdas, Tomave, Rio Mulato, Sevaruyo, Huari, Poopo, Oruro. These are the dots on our line through Bolivia so far. Sadly, we will be through Bolivia after just one more trek. Although able to celebrate our half-way mark, a huge happening for us, Bolivia has treated us well and I’m not quite ready to leave it yet.

Here’s one reason: the other day I was walking across Lake Poopo (Lago, actually), and my feet simultaneously sunk about a foot deep, each, in the mud that is the bottom. I lost my balance and fell, getting myself entirely soaked, at night, at 12,000-some feet, and along with myself, I soaked my music, my little mp3 player, my lifeline on the really rough, long, painful stretches of the hike. I was quite bummed. Back home, that probably would have been curtains for my little musical device, but here in Bolivia, they have lots of things that make sense, like people who fix things. Every block in every city has repair people, of shoes, of clothes, of electronics, of watches, whatever needs fixing. And these fix-it people (we’ve been to many) are exceptionally competent and quick and affordable. I now have my music revived and kicking for less than four bucks. Shoes can last an extra two months for a couple dollars and a half-hour wait. Pants, an even longer life extension. It’s beautiful. Whereas at home it’s common to chuck or donate objects in various states of disuse, here, they are easily and commonly given another chance. This reduces waste (which is a good thing, since unfortunately dump=river here), is much easier on the wallet, and encourages a different way of thinking about possessions as things to be valued for years and not disposables.

But that is just one small reason that Bolivia is great. Also, the land is spectacular. In a country one and a half times the size of Texas, you get the Canyonlands-of-Utah-caliber rock formations, 21,000 ft. spectacularly beautiful peaks, and dense jungles. The cities have cobblestone streets, beautiful colonial-period cathedrals, great food, completely modern communications, and a broad mix of folks. Do I sound like a Lonely Planet intro paragraph here? Most likely not, actually, since the first thing Lonely Planet says is how poor a country Bolivia is.

Had that not been drilled into my head by every guide and article about the country, I would have no idea from actually being here and walking through it that that is the case. It may have the worst exchange rate with the dollar, but in and of itself, I’ve found it to be completely comfortable and lovely. Indeed, everything is exceedingly cheap here when thinking in terms of dollars (or cents, often), but equal or better in quality to things anywhere else. The people we have come upon out on the puna who make their living herding sheep and living in mud-brick houses and cooking over fires may not have a dime worth of Boliviano centavos, but they certainly have good food that they raise and grow themselves, and which they are exceptionally eager to share, strong families, and practically free health care. So are they poor? I certainly don’t think so. Gregg and I were on a beeline toward Tomave (or where Tomave was supposed to be anyway) over a huge open pampa, when we passed fairly close to a isolated house and accompanying out-structures. One of these structures was a ring of branches serving as a wind block, as inside the ring, a family sat cooking around a fire. As we neared it, all we could see, however, were a sequence of faces popping up over the edge of the ring and then settling back down. We neared to say hi. The mother yelled at us to come join them and sit down, scrambling to get a block and sheep pelt covering for us to share so we didn’t have to sit on the ground. We sat and looked back at about seven faces, five kids ranging from one to twelve and two women. The mother yelled to her eldest son to get bowls and spoons from inside. He ran in the house, leaving the door open to reveal two more kids and some goats on the table. The bowls were immediately filled with soup upon their arrival in the circle and handed to Gregg and I. We protested, not wanting to take their food and wanting to limit our time not hiking. The refusal was refused, outright. We were eating soup, and it was great. We talked with the family (minus the father, who was out working) about what we were doing and about their school and language and learned a few Quechua words (they were obviously completely bilingual), and then received the second course of rice and potatoss and lentils and meat, also without choice, and also excellent. We followed this with a little geography/map and compass session, with our map of Bolivia on the ground and lots of intrigued faces pouring over it and fingers pointing to familiar names and places. We regretted not being able to hang out and talk the rest of the day with them, but we walked away after goodbyes feeling like we had been gifted a reminder of what makes this experience what it is: wonderful.

The walking as of late, has been exceptionally flat. We are still high up in the Andes, but we have been crossing our share of dried-up lake valleys. Flat walking means more miles every day, and it also means more pain for the body due to the repetitive motion and impact. Until you do something like this, you wouldn’t expect that we would crave uneven terrain and ups and downs, but indeed, flat does not turn out to be easy. Lago Poopo, which I mentioned earlier, is part of what was once a huge lake covering much of the Altiplano from Ecuador to Chile and including the present Lake Titicaca and Salar de Uyuni. Now, however, the salt lake ranges from shallow to completely dry, with mud cracks and salt crystals and all. We thought, and were backed up by advice from locals, that these conditions meant that we could walk across the “lake” as it is shown on our map, taking a much more direct route toward La Paz and Titicaca. All started well, and sure enough, it was dry and fast walking for a few days. Once we got to the supposedly narrowest portion of the lake, though, things got a bit wetter. Starting with mud and puddles, we kept at it. The puddles transitioned into canals that needed to be waded across and the mud turned increasingly stickier and deeper. Soon we were surrounded by water up to our ankles and pushing through reeds. Houses stood abandoned periodically on small islands, which we stopped at to warm our feet. The water deepened, the mud below it deepened as well. Mid calf, knee, mid-thigh, waist. The sun was setting and it was getting colder, and we were more and more aware of how S.O.L. we were going to be if this trend continued. Coming to a row of occupied houses on a slightly larger dry patch, we tried to ask some sheep herders if it would be possible to cross, as we were told it was, and as our map indicated by showing a road over the area marked as lake. Unfortunately for us, the women only spoke Quechua and we were unable to get a clear answer through arm gestures. We then came upon a younger man, who, in perfect Spanish, told us that we needed to turn around, that the lake was, indeed, impassible right now on foot. As his cows swam across a channel next to us, illustrating his point, we turned around, defeated, and bracing ourselves for a cold and muddy return through what we had just made it through, this time, without the sun. It was soon into this next portion that I was half-swallowed by lake muck and opaque water. We made it, however, to the town of Poopo, some 7 km away, where we got a hot dinner and argued with the only alojamiento in town that they did indeed have beds since nobody else was staying there. After some time, the kid running the place admitted that we were right and took us from the room with the floor to the very empty room with the beds. Floors and ground are usually just fine, but after falling into a lake and hiking wet and muddy through the dark, that foot-high separation from the tierra was a comfort.

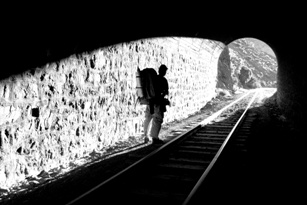

Wanting to make up our lost time due to our now-longer route, we decided to walk the entire 30 miles to Oruro the next day and night. The day lagged on, but the night turned out to be one of my favorite hikes so far. As our map showed, the railroad did indeed go right over the lake. On a few-meter-wide land bridge that stretched nearly ten miles, the tracks led straight toward town, a few lights in the distance as we set out. With water on both sides of us, we walked with the full moon looking over our right shoulders. More birds than I have ever seen in one area played and splashed and sang on both sides of us. Flamingos strolled by and ducks sprinted over the lake surface away from us as we neared them. The night was quite surreal and magical, following these steel rails the whole way across this expanse of water, taken over by avians. Some hours later, we arrived. Finally hitting the 30 mile mark, and feeling pretty good for it, and finally timing a night hike to correspond with a full moon.

From here we head out toward La Paz, where we will be just shy of the Peruvian border, and halfway through with this project. That will bring much in the way of feeling and reflecting, but that’s for next time.

Thanks for keeping up with us. My love to my family, as always. And it’s great to hear from you all, it keeps us feeling connected, so drop a line. Enjoy spring, you northern hemisphere folks!