Caping, Calving, and Carving

By Gregg Treinish

March 14, 2008

We managed to escape from the clutches of Cochrane in the afternoon,

the usual internal debate of whether to stay for one more beer or to go

taking place like it always does on the way out of town. The week

ahead looked promising, the maps showing a good trail the whole

way, no roads, and no major obstacles that we'd have to navigate

around. We were excited to have a third along. We had met

Ross a week earlier while hiking through Cerrro Castillo

National Park, he was the very first gringo (along with his hiking

buddy Thatcher) that we had met backpacking on his own in over 610

days of hiking. He had decided to join us for the

section and we were stoked to have someone else to talk to, even

if for only a week. As we left town it quickly became

clear that in the Chilean government's race to show the rest of

the world how advanced it is, they have built yet another new

road where only trail had existed before. Reluctantly, and

without much choice in the matter, we followed it hoping that

maybe it wasn't yet complete, that we would still have the majority of

a week to hike in nature. Twenty kilometres or so later, directly

across from the San Lorenzo glacier and icefall, the largest peak,

and one of the most spectacular in Patagonia, the military stopped

their placement of dynamite and turned off the engines as

we walked by. The road had ended, leaving the

valley virgin for now. We realized that we may be the last

gringos to have the privilege to walk through the valley before

the new Carrertera Austral destroys it. Seems that the other

new Carrertera Austral was not good enough, and that they need a second

one to... well I don't really know why, neither did anyone

building it. The building goes on none-the-less.

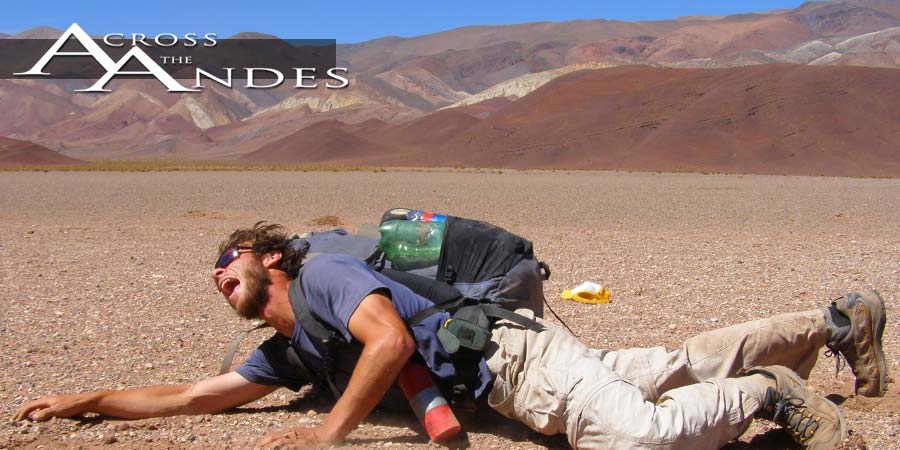

Upset, and cursing the advancement project, we made our way further up

the valley. Soon, the sounds of bulldozers and drilling

were far below and we began to realize exactly how lucky we were

to be there before the destruction. It was impossible to move

more than a hundred steps before having to stop and appreciate what was

around. On this trip, change has been the one constant, often

within the course of a day as we move east to west or from elevation to

the depths of the valleys below we move from glaciers to

jungles. The change that we were experiencing as we moved

south through the Lorenzo Valley was a more important

one. Now looking around to the peaks above us, seemingly

every single one was covered in the blue ice of glaciers. Have we

really come this far? It is hard to believe that we have walked

from the equator to the line that means everything to the south is

glaciated; it was a good feeling, one that makes us feel

close to the end, a good motivator if you will. Throughout

that week with Ross along for the ride, as we trudged our way through

knee-deep flooded trails, through overflowing rivers, through mud, and

overgrown prickers on the trails, ice and water continued

to assert its grip on the land around us until by the end of

the week not a single peak was without a crevassed mass of

ice carving the top of it.

In this past month and a half, walking through those

glacially-carved lands, there have been several ups and

downs. Near the beginning of it, Deia and I were looking at

another sight, one that in our heads we knew should be

mind-blowing, one that we knew would have moved us to tears if we had

been dropped in that spot 21 months ago. It didn't move us to

tears, in fact, aside from just knowing that it was really

beautiful, there was really very little impact that place had on either

of us. We talked about it, wondering if we had simply seen too

much, developed a tolerance against the feelings that make hiking

so special. After what has now been 21 months of solid walking,

solid awe at what we have been experiencing, we were

beginning to think that we could be awed no more. For me

that though was a bit scary, would I ever feel like I need to hike

again? Would time away make it that inspiring to see a peak

again? These are not thoughts someone who wants to make a career

of hiking can have, it is not okay. We talked a lot about how we

are both done, ready to finish, wanting to be in other places,

with friends, with family, ready to close this chapter. It's not

that we don't love the hike, not that we are fed up, not that we

weren't extremely excited for the promise of what was ahead, just that

we were ready, spent, tired of struggling every day, and missing home a

lot. We have been in Patagonia, the combined region of

Southern Chile and Argentina, for more than three months now. We

have been impressed with the pristine natural beauty that has been

around us all the while, and until this past section, it was hard to

apreciate how far we have really come, that we have arrived in a land

that we have been walking towards for so long now. Patagonia had

been amazing, still, it hadn't yet captured our hearts. The

desire to finish began to outweigh the drive to go on. It became

harder to get up everyday and the feeling that this was more of a job

than an experience was strong and becoming unbearable. It

is often easy, as we are walking, to think back to hikes we have done

earlier on. The detail of what we can remember about each and

every day over the last two years is pretty incredible. I

remember that tree that we ate lunch by, what I ate by it even.

If you have been hiking, you know what I mean, time goes slower,

memories are linear. If it has a before and after to go with the

memory the human brain retains with an incredible accuracy. I

wonder though, in five, ten, or even twenty years, how vivid these

memories will be, how long will I actually be able to picture myself

back on the same rock, looking at the same ridge, and know that a

certain jagged difference makes that spot unique to all others on

earth. I am sure that several details will fade, they already

have from some hikes that I have done earlier in my life. What I

know is that several moments that have passed since that view, since

feeling so entirely done, are moments that will stay with me for a

lifetime. It has always been amazing to me how quickly emotions,

feelings, attitudes can change while hiking. How

the littlest thing, the smallest turn of events can get you

going again and make it fun. What we have seen in the last month

and a half was no small thing, no small change.

We left Mancillo late in the day, really without knowing how far it

would be until we would get our first views. It had been built up

in my head for so long, there was no way that it could really be that

spectacular. Chances were that we wouldn't get clear views anyways, we

had heard that it is always shrouded in cloud, that it is rarely

without its blanket hiding it from the world. I wasn't expecting

much. We climbed steadily as the sun inched its way closer to the

horizon and the shadows grew longer all around. Soon the forest

of lenga and ñire was lit just right, that magic light the hour or so

before the sun goes away for the evening. The weather was

great, maybe we would get a view yet, just maybe we'd be able

to see this thing after hearing about it for so incredibly long.

I climbed slowly on the dirt track as it wound through the forest, my

eyes scanning the ground and following the tiny lizards scurrying about

my feet and passing the time by kicking a stone ahead then again and

again until it fell to the side of the trail and I was forced to find a

new one to play with. Had we actually reached this

place that we had read about and listened to tourists talk about for so

long now? Was I really about to see something I first heard of in

a climbing documentary so long ago and was blown away by even

then? I was excited just to be near such a respected mountain

despite the doubts of actually being able to see it. I looked up

for a second, partially to see where I was headed, partially to see how

far it was to the pass. Immediately, I looked back down, as

what I had just seen failed to register. Nah, I said to myself,

that is impossible. Double-take. Instantaneously, I was on

my knees, floored, gasping for breath. Tears flooded my eyes,

that thing, wha- wha- what the hell is that? Mt. Fitzroy stands

10,262 feet high, not that big right? Well, when you consider

that the sheer granite wall, the longest wall in the world rises 6,401

feet straight up out of the ground, it is huge, the biggest, the

gnarliest, and to see it outside of the pictures, right there in front

of me was flooring. I turned around to see Deia meandering

up the trail behind me, passing the time much as I had without the

knowledge of what was ahead of her. She looked up at me, and I

think she knew, after all I was on my knees and clearly

had been struck down by the force of something mighty. She took a

few more steps, and I watched her face change from idle to shocked

in a mere second. Laughter filled the air, giggling out loud, we

raced towards a clearer view. Out of every mountain I have

seen, never has it been this hard to believe that what I was looking at

was real. Fitzroy looks like a fairytale, it is a dream. As

long as I live I will never forget that first sight of it. It is

burned into my brain. It is the reason I will forever continue

exploring.

While Fitzroy was certainly special, it was by no means all that

we have seen this month that is worth mentioning. The Southern

Patagonian Icecap is the third largest continental concentration of

ice in the world, Antarctica and Greenland the only ones

bigger. It covers a distance of more than 210 miles

north to south and covers an area of more than 10,490 square

miles. Pouring off of the giant blanket of ice are glaciers, the

biggest glaciers in South America. For a long time before we

had actually seen the Ice Cap, I was literally dreaming of

standing above a sea of ice, looking out for miles over a white

forbidden land. I got my wish.

We left the road and began up the Electrico valley. Less

people than I expected to see in one of Patagonia's two main

parks. It was an easy stroll taking two hours or less to

reach the refúgio. It would be a steep climb from there so

we stopped to grab some food and rest at a bit. It was a reminder

of how special of a place we were in when in the camp we met

John Braggs, a celebrated American climber with many first

ascents on his resume. We left the camp and began steeply

up. It was but an hour when we found ourselves at the foot of

Fitzroy and overlooking the Marconi Glacier flowing off of the Ice

sheet. We continued ascending. Soon we were at a small lake

at the base of the Fitz, icebergs filled the frigid waters, more

importantly we were beginning to crest the horizon of the ice

sheet. We continued ascending, now using both hands and feet, as

we climbed over loose scree, very loose scree, scree so loose that

often the entire area around us would move and begin sliding down the

mountain as we skirted to the left or right to avoid being cascaded

down the steep face. It had been our goal to see the ice sheet at

sunset, with seven hours of daylight, we surely had enough time.

Now with only two hours left until we would have to turn around,

our arrival on the Cerro Electrico ridge was certainly in doubt.

We got to a low col and continued the steady climb

upwards, scrambling all the while along a knife edge ridge, until

finally we turned around and the vastness spread out before us.

To explain what it was like to sit in those mountains, to explain

the impossibility of the peaks that surrounded us would be a challenge

at best. I think that maybe for the first time I sat there on

that edge watching Deia scramble up the knife edge ridge behind me

and perhaps for the first time I really understood what I was looking

at, how much it really means to be looking at the Ice Cap. I

remember a similar moment that I had on the Appalachian Trail, the

moment when I actually let myself believe that I may finish what I set

out to accomplish so long before. The concept of not doing this

anymore is something that really just doesn't compute in my head.

After so many months, so much struggle, it has just become life, I will

certainly miss what I have been doing, and yes I am ready to move on,

but in that moment looking out over the ice field, there is no feeling

that could make what we have been doing more worth it and nothing more

symbolic of how far we have really come.

The list goes on and on, constantly this section has wowed us,

constantly we are moved, overcome with emotion, and appreciative to be

in a place so spectacular, still so pristine, so wild. Patagonia

is such a special place unlike any other on earth. The granite

spires rising from what seems to be every peak, the glaciers so

impossible to comprehend the mass of. Sitting now with just over

340 miles to go, it still has not even begun to sink in that we are

going to be finishing this quest in just under five weeks (assuming all

goes well). For so long this has been our struggle, our goal, our

everything. What next? As you might imagine we have been

talking a lot about the next step, the next move. At this point,

we haven't come up with any concrete plans. There are a lot of

people we want to visit, a lot of catching up we want to do.

We will be leading a trip or two this summer, so, if you or

anyone you know wants to go backpacking with us, email us at

thediscoveryguides@gmail.com In addition we look forward to speaking at

various hiker gatherings, schools, tradeshows, etc. For now we

will remain focused on the task at hand. We will be crossing into

Tierra Del Fuego in just under two weeks. We are filled with hope

of seeing penguins, still keeping our fingers crossed for a puma in

daylight, and very much looking forward to reaching the lighthouse at

Cabo San Pio, the southern-most point of Tierra Del Fuego. The

next time we write, we will be done with this chapter, a concept that

although I still cannot comprehend, I think I am ready for.